An Essay Touching upon a Few of the Many Reasons Why the Current Standards-and-Testing Approach Doesn’t Work in ELA

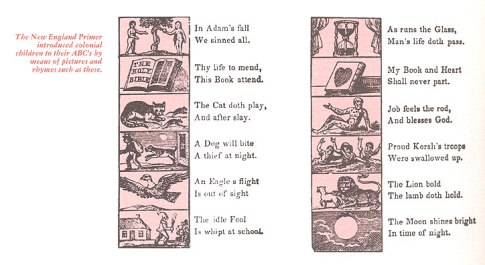

NB: For all children, but especially for the one for whom learning to read is going to be difficult, early learning must be a safe and joyful experience. Many of our students, in this land in which nearly a third live in dire poverty, come to school not ready, physically or emotionally or linguistically, for the experience. They have spent their short lives hungry and/or abused. They lack proper eyeglasses. They have had caretakers who didn’t take care because they were constantly teetering on one precipice or another, often as a result of our profoundly inequitable economic system. Many have almost never had an actual conversation with an adult. They are barely articulate in the spoken language and thus not ready to comprehend written language, which is merely a means for encoding a spoken one. They haven’t been read to. They haven’t put on skits for Mom and Dad and the Grandparents. They don’t have a bookcase in their room, if they have a room, brimming with Goodnight, Moon; A Snowy Day; Red Fish, Blue Fish; Thomas the Tank Engine; The Illustrated Mother Goose; and D’Aulaires Book of Greek Myths. They haven’t learned to associate physical books with joy and closeness to people who love them. In the ambient linguistic environment in which they reached school age, they have heard millions fewer total numbers of words and tens of thousands fewer unique lexemes than have kids from more privileged homes, and they have been exposed to much less sophisticated syntax. Some, when they have been spoken to at all by adults, have been spoken to mostly in imperatives: “Stop that! I told you to stop doing that or you’ll get a spanking. Go outside and play!” (Compare the middle class, “See the leaves? Funny looking, huh? This is called a Gingo tree. Can you say, Ginko? Great. These trees come all the way from China, which is all the way on the other side of the whole wide world!”) Children from low-positive-stimulus homes desperately need compensatory environments in which spoken interactions and reading are rich, rewarding, joyful experiences. If a child is going to learn to read with comprehension, he or she must be ready to do so, physically, emotionally, and linguistically (having become reasonably articulate in a spoken language). Learning to read will be difficult for many kids, easy for others. And often the difficulty will have nothing to do with brain wiring and everything to do with the experiences that the child has had in his or her short life. In this, as well as in brain wiring, kids differ, as invariant “standards” do not. Kids who haven’t had such experiences need one-on-one conversations with adults who care about them. They need exposure to libraries and classroom libraries filled with enticing books. Kids need to be read to. They need story time. They need jump-rope rhymes and nursery rhymes and songs and jingles. They need social interaction using spoken language. They need books that are their possessions, objects of their own. They need to memorize and enact. And so on. They need fun with language generally and with reading in particular. They need the experiences that they never got. And so, the mechanics of learning to read should be only a small part of the whole of a reading “program,” and reading programs must grok that kids differ as the magic formulae of Education Deformers and Self-Proclaimed Education Pundits do not. However, this essay will deal only with the mechanics part of early reading instruction. That, itself, is a lot bigger topic than is it is generally recognized to be.

Permit me to start with an analogy. As a hobby, I make and repair guitars. This is exacting work, requiring precise measurement. If the top (or soundboard) of a guitar is half a millimeter too thin, the wood can easily crack along the grain. If the top is half a millimeter too thick, the guitar will not properly resonate. For a classical guitar soundboard made of Engelmann spruce (the usual material), the ideal thickness is between 1.5 and 2 mm, depending on the width of the woodgrain. However, experienced luthiers typically dome their soundboards, adding thickness (about half a millimeter) around the edges, at the joins, and in the area just around the soundhole (to accommodate an inset, decorative rosette and to compensate for the weakness introduced by cutting the hole).

To measure an object this precisely, one needs good measuring equipment. To measure around the soundhole, one might use a device like this, a Starrett micrometer that sells for about $450:

It probably goes without saying that one doesn’t use an expensive, precision tool like this for a purpose for which it was not designed. You could use it to hammer in frets, but you wouldn’t want to, obviously. It wouldn’t do the job properly, and you might end up destroying both the work and the tool.

But that’s just what many Reading teachers and English teachers are now doing when they teach “strategies for reading comprehension.” They are applying astonishingly sophisticated tools—the minds of their students—in ways that they were not designed to work, and in the process, they are doing significant damage. Leaving aside for another essay the issues of physical and emotional preparedness, to understand why the default method for teaching reading comprehension now being implemented in our elementary and middle-school classrooms fails to work for many students, one has to understand how the internal mechanism for language is designed to operate.

Linguists, since Chomsky, use the phrase Language Acquisition Device, or LAD, to refer to the innate mechanism—hardwired into the human brain—for learning spoken language, including grammar and vocabulary. The parts of the brain that carry out this learning, some of them localized and some not, coordinate with other parts of the brain that do pattern recognition (for decoding) and long-term storage and retrieval of knowledge about the world (for recognizing context and reference) to form the complex mental tool for comprehending texts. Sadly, some English teachers, Reading teachers, and Education professors and many curriculum coordinators, test makers, leaders of textbook companies, and bureaucrats and politicians who mandate state testing of reading typically understand almost nothing of how the internal tools for comprehending a text work, for almost to a person, they know very little of contemporary linguistic and cognitive science, and so instead of basing their instruction and assessment on those sciences, they fall back on unexamined folk ideas—established habits of the tribe—and mandate or implement comprehension instruction and assessment that can most charitably be described as prescientific folk-theory and superstition. The internal tool—the language mechanism of the student brain—is not designed to work in the ways in which “reading comprehension specialists” fielding “reading strategies” are asking students to use it. Ironically, the person with the doctorate in Reading Comprehension from an education school is the one most likely to be wedded to prescientific “strategies-based” techniques (pedagogy) and materials (curricula and assessments). Such people direct reading instruction in our schools, and the result is predictable: lots of kids who might have been readers but don’t typically read on their own because they can’t—because for them reading is too difficult to be enjoyable.

The Persistence of the Prescientific

In the past fifty years, we have had dramatic scientific revolutions in both linguistics and in cognitive psychology. We now know a lot about how language and knowledge are acquired and about how people make sense of texts, and almost none of this science has made its way into instructional techniques and materials. A digression on the history of physics will provide an illuminating contrast to the current state of much reading comprehension instruction.

In their brilliant and accessible little book The Evolution of Physics, Albert Einstein and Leopold Infeld describe how Galileo used a thought experiment to overturn the then roughly 1700 -year-old Aristotelian notion that objects in motion contain a motive force that is used up until they come to rest. Galileo imagined using oil to make the object travel further. Next he imagined using a perfect oil that would perfectly reduce the friction acting on the object. The result was the idea codified in Newton’s First Law of Motion: objects don’t move until they use up their force; instead, they persevere indefinitely (forever) in uniform motion until they are acted upon by an external force that changes their motion. The Aristotelian notion is entirely intuitive. The Galilean/Newtonian notion is quite counterintuitive. However, the Aristotelian notion is false, and the Galilean/Newtonian one true. Aristotle’s was a prescientific folk theory of motion. It made sense to people, but it was wrong, wrong, wrong, and the development of modern technology and science was not possible until it was overthrown.

Other folk and pseudo-scientific theories of physics and astrophysics have held sway throughout the centuries—the theory that fire is the release, during combustion, of an element called phlogiston; the theory that light propagates as waves in an invisible medium called the ether that fills space; the theory that heavier objects fall faster than light ones do; the theory that the Earth is flat; the theory that the sun travels across the sky; the theory that the Earth is at the center of the universe and that planets revolve around it in epicycles—spheres within spheres. All these notions made sense based on people’s everyday observations and their intuitive thinking about those observations, and all were absolutely wrong.

Now, imagine that you go into a high school in the United States today (in 2019), pick up an introductory physical science text, and find that it teaches the Aristotelian theory of motion, the phlogiston theory of fire, and the waves-through-ether theory of light propagation. Suppose the space science textbook in that school teaches that a flat earth sits at the center of the universe and that planets move around it in epicycles. You would be shocked, appalled, scandalized. But, of course, this would never happen. Our physics textbooks try to teach elementary contemporary physics.

But walk into almost any K-12 school in the United States today and you will find instructional and assessment techniques and materials that are built upon prescientific, folk theories of grammar, vocabulary acquisition, and reading comprehension that are completely at odds with our contemporary scientific understandings of these. Walk into teacher training institutions and you will find, typically, that the prescientific, folk theories are being taught. Pick up any state or district interim reading assessment, and you will find that they were built on these folk theories.

What Reading Comprehension Involves

In order to read a text with comprehension, one needs to be able to

- interpret automatically (unconsciously and fluidly) the symbols being used (the phonics component of decoding). Note that this crucial precursor for reading comprehension requires that the student be able to recognize, quickly and without effort and, indeed, without conscious rehearsal of the fact that he or she is doing so, the roughly 42 separate sound-symbol correspondences of written English (the actual count is higher, but this rough number is sufficient for the purposes of phonics instruction).

- parse automatically (unconsciously and fluidly) the morphology and syntax of the sentences (the grammar component of decoding). Morphology is the rule-based combination of minimal, meaningful or functional word parts, or morphemes, into words. Syntax is the rule-based arrangement of words and phrases to form well-ordered, grammatical statements in a language. (In the rest of this essay, when I use the term syntax, I will be referring to syntax proper and to morphology; sometimes I will mention both explicitly when I think it particularly important that both be considered.) Note that this crucial precursor for reading comprehension–grammatical fluency–requires that the student be able to parse, quickly and effortlessly and usually without consciousness that they are doing so, many thousands of syntactic forms.

- interpret the meanings of the words and phrases (based on what they refer to and how they are used in relevant real-world contexts). Note that this crucial element of reading comprehension depends, fundamentally, upon specific, related world knowledge in the domain that the text treats. A contemporary philosophy text might use words like defeasible, propositional calculus, modal operator, zombie, counterfactual, supervenience, indexicality, and grue, and one will have to know how these words are used in contemporary philosophy and quite a bit about how they are related to one another in order to understand the text at all.

- recognize much of the kairos, or total context, of the text (the who, what, where, when, why, and how of its creation, including its genre, or type, the concerns of its author, and its literary and rhetorical conventions). Note that this crucial element of reading comprehension depends upon prior experience with and inductive learning about similar extra-textual elements. (Inductive learning is learning from experience, the kind in which we generalize, consciously or unconsciously, from specific instances. Most learning is inductive.)

Let’s look at each of these in turn to learn what science now tells us about them and how our reading comprehension instruction goes wrong.

Phonics and Reading Comprehension

This is the one bright spot in our reading instruction, an area where practice has caught up to scientific understanding. However, it’s taken us a while to get there. In the middle of the last century, we were using what is known as the “Look-Say” method for teaching kids to decode texts. This method was enshrined in such curricula as the Dick and Jane readers. The method was based on a now-discredited Behaviorist theory that saw language learning as repeated exposure to increasingly complex language stimuli paired with ostensive objects (in the case of the Dick and Jane readers, with illustrations). See Dick run. Dick runs fast. See, see, how fast Dick runs. The theory of language learning by mere association of the stimulus and its object dates all the way back to St. Augustine, who wrote in his Confessions:

When grown-ups named some object and at the same time turned towards it, I perceived this, and I grasped that the thing was signified by the sound they uttered, since they meant to point it out. . . . In this way, little by little, I learnt to understand what things the words, which I heard uttered in their respective places in various sentences, signified. And once I got my tongue around these signs, I used them to express my wishes.[1]

It’s an intuitive theory, like the theory that moving objects use up their force until they stop, but like that theory, it’s wrong. Look-Say was a flawed approach because it was based on a false theory of how language was acquired. The fullest exposition of that flawed theory can be found in B.F. Skinner’s Verbal Behavior (1957). In 1959, Noam Chomsky, who has done more than anyone to create a true science of language learning, delivered a devastating blow to behaviorist theories of language learning in a seminal review of Skinner’s book.[2] Basically, Chomsky described aspects of language, such as its embedded recursiveness and infinite generativity, that, like jazz improvisation, cannot be explained solely on the basis of responses to stimuli. More about the Chomskian revolution later.

Toward the end of the last century, hundreds of thousands of educators around the country embraced something called “Whole Language instruction.” Proponents argued that it wasn’t necessary to teach kids sound-symbol correspondences because language was learned automatically, in meaningful contexts. The idea was that one simply had to expose kids to meaningful language at their level, and the decoding stuff would take care of itself, in the absence of explicit decoding instruction. Those states and school districts that adopted Whole Language approaches saw their students’ reading scores fall precipitously. Education is given to such fads and to such disastrous results. The learning of Japanese kanji provides a useful hint about learning to read entirely based upon whole-word recognition. Japanese has not one but three (!) phonetic writing systems–hiragana, katakana, and romaji–but it also has characters, called kanji, adapted from Chinese characters, that stand for whole words. These have to be memorized individually. The average Japanese reader knows only about 2,000 kanji, far fewer than the number of spoken words that he or she knows and far fewer than the total number in the language. (One dictionary contains 85,000 kanji, though the usual number given is around 50,000!) This is a serious problem. So, learning individual words, one by one, is not ideal. The Japanese, who are forced by their writing system to learn to read much of their language in this way, learn to read only a tiny fraction of words in their language. That said, the analogy between learning kanji and whole-word recognition isn’t clean. Why? Well, consider this:

Toward the end of the last century, hundreds of thousands of educators around the country embraced something called “Whole Language instruction.” Proponents argued that it wasn’t necessary to teach kids sound-symbol correspondences because language was learned automatically, in meaningful contexts. The idea was that one simply had to expose kids to meaningful language at their level, and the decoding stuff would take care of itself, in the absence of explicit decoding instruction. Those states and school districts that adopted Whole Language approaches saw their students’ reading scores fall precipitously. Education is given to such fads and to such disastrous results. The learning of Japanese kanji provides a useful hint about learning to read entirely based upon whole-word recognition. Japanese has not one but three (!) phonetic writing systems–hiragana, katakana, and romaji–but it also has characters, called kanji, adapted from Chinese characters, that stand for whole words. These have to be memorized individually. The average Japanese reader knows only about 2,000 kanji, far fewer than the number of spoken words that he or she knows and far fewer than the total number in the language. (One dictionary contains 85,000 kanji, though the usual number given is around 50,000!) This is a serious problem. So, learning individual words, one by one, is not ideal. The Japanese, who are forced by their writing system to learn to read much of their language in this way, learn to read only a tiny fraction of words in their language. That said, the analogy between learning kanji and whole-word recognition isn’t clean. Why? Well, consider this:

wohle lnagauge ws an apporach to lraernig to dcode polpaur dacedes ago

Based on context and opening and closing graphemes and general knowledge of the spoken language, readers can recognize words. So, there are clues in written English not found in kanji, though most kanji are synthetic (built up of other kanji), and those provide clues as well.

A little knowledge of linguistic science would have prevented the debacle that was Whole Language. The best current scientific thinking is that language emerged some 50,000-to-70,000 years ago. For many thousands of years, people learned to use spoken language without explicit instruction. However, writing is a relatively recent phenomenon. It’s been around for only about 5,000 years (It emerged in Mesopotamia around 3,000 BCE, in China around 1,200 BCE, and in Mesoamerica around 600 BCE). Both the Look-Say and Whole Language proponents failed to recognize that spoken language has been around long enough for brains to evolve specific mechanisms for learning it automatically, in the absence of explicit instruction, but that this is not true of writing. There is no evolved, dedicated internal mechanism, in the brain, specifically wired for decoding of written language, as there is for spoken language. Instead, decoding of written symbols (graphemes like f or ph) and associating them with meaningful speech sounds (phonemes like /f/) is most easily learned, by most kids, from explicit instruction. Some children are good enough at pattern recognition and get enough exposure to grapheme-phoneme correspondences (GPCs) to be able to learn to decode in the absence of explicit instruction in interpretation of those correspondences. Such decoding appropriates general pattern recognition abilities of the brain and puts them to this particular use. But even some of those kids–ones who learned to decode without explicit instruction–sometimes don’t develop the automaticity needed for truly fluent reading. There is now no question about this: There is voluminous research showing that many, perhaps most, students have to be taught phonics (sound-symbol correspondences) explicitly if they are to learn to decode fluently. For excellent reviews of this research, see Diane McGuiness’s Early Reading Instruction: What Science Really Tells Us about How to Teach Reading. Cambridge, MA: Bradford/MIT P., 2004, and Why Our Children Can’t Read and What We Can Do about It: A Scientific Revolution in Reading. New York: Touchstone/Simon and Schuster, 1999.

The Look-Say advocates got their ideas from simplistic Behaviorist models of learning, but where did the Whole Language people get theirs? Well, from listening at the keyholes of linguists. As sometimes happens in education, professional educators half heard and half understood something being said by scientists and applied it in a crazy fashion. What they half heard was that linguists were saying that language is learned automatically. The part that they missed is that the linguists were talking about spoken language, not written.

The upshot: In order to be able to comprehend texts, there is a prerequisite: automaticity with regard to decoding of GPCs. Where does one get this automaticity? Well, for many kids, from explicit phonics instruction. This is a lesson that we have learned. Classroom practice has caught up with the science; almost all elementary schools now use, successfully, in the early years, an explicit early phonics curriculum, typically as part of a “balanced literacy” program; and all the major basal reading programs in the US have strong phonics components. That’s the good news. Now for the rest, which is not so good.

Grammatical Fluency

In the last decade of the twentieth century, the U.S. Department of Education committed billions of dollars to an initiative called Reading First, with the aim of improving reading among schoolchildren nationwide. It’s a mark of how scientifically backward and benighted some of our professional reading establishment is that when the directors of this program consulted “experts” and asked them to outline the areas of focus to be addressed by Reading First (and assessed by reading examinations), those “experts” included among items to be addressed by the program

students’ decoding skills (phonemic awareness and phonics),

vocabulary, and

comprehension

but completely ignored grammatical fluency. However, and this ought to be obvious, written texts consist of sentences that have particular syntactic patterns. If students cannot automatically—that is, fluently and unconsciously—parse the syntactic patterns being used, then they might have some idea what the subject of the text is, but they won’t have a ghost of a chance of understanding what the text is saying.

Syntactic complexity is, of course, a significant determinant of complexity and readability. Consider the opening two sentences of the Declaration of Independence:

Sentence One:

When in the Course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with one another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare which impel them to the separation.

Sentence Two:

We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness—that to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, —that whenever any form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundations on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

These sentences contain a few vocabulary items that might be challenging to young people—impel, endowed, and unalienable—but for the most part, the words used have high frequency and present no great challenge. The most significant stumbling block for comprehension of these sentences is their syntactic complexity. The first sentence consists of a long adverbial clause, beginning with When in the Course and ending with entitle them, that specifies the conditions under which it is necessary to take the action described in a main clause that follows it (a decent respect . . . requires). The second sentence consists of a main clause that introduces a list in the form of five clauses, each specifying a truth held to be self evident. (Note that current readability formulas use sentence length as an extremely rough stand-in for syntactic complexity. This sort of works, but only sort of. Sentences can be short and syntactically complex or complex in many other ways, in their references, their use of figures, their challenge to conventional thinking, and so on. That’s one reason why readability calculations should be taken with a big grain of salt.) Here’s the point: the student who can’t follow the basic syntactic form of these sentences from the Declaration will be completely lost. He or she won’t understand how a given idea in one of these sentences relates to another idea in them (for that is what syntax does; it relates ideas in particular ways). An automatic, fluid grasp of the syntax of a sentence is critical to comprehending what it means. What’s true of complicated sentences like these from the Declaration of Independence is true of sentences in general. One can’t comprehend them if one cannot parse their syntax automatically (quickly and unconsciously). Grammatical competence is one of the keys to decoding, and decoding is a prerequisite for comprehension.

So, are schools today ensuring via their instructional methods and assessments that students are gaining the automatic syntactic fluency necessary for decoding? Well, no. In fact, they are implementing materials based on a folk theory of grammar that predates the current scientific model of language acquisition. Consider, for example, this gem from the backward, puerile Common Core State Standards (CCSS) in English Language Arts, which provide the current goals and, disastrously, the de facto outline for instruction in English and reading. According to the CCSS, an eighth-grade student should be able to

Explain the function of verbals (gerunds, participles, infinitives) in general and their function in particular sentences. (CCSS.ELA-Literacy-L.8.1a).

The other grammar-related “standards” in the CC$$ are similar. They all show that at the highest levels in our educational establishment, there is a complete lack of understanding of what science now tells us about how the grammar of a language is acquired. The standard instantiates a prescientific, folk theory of grammar that assumes that grammatical competence is explicitly acquired and is available for explicit description by someone who consciously “knows” it (“Explain the function”).

This standard tells us that students are to be instructed in and assessed on the ability a) to explain the function of verbals (gerunds, participles, and infinitives) in general and b) their function in particular sentences. In order for students to be able to do this, they will have to be taught how to identify gerunds, participles, and infinitives and how to explain their functions generally and in particular sentences. In order for the standard to be met, these bits of grammatical taxonomy will have to be explicitly taught and explicitly learned, for the standard requires students to be able to make explicit explanations. Now, there is a difference between having learned an explicit grammatical taxonomy and having acquired competence in using the grammatical forms listed in that taxonomy. The authors of the standard seem not to have understood this fundamental principle from contemporary linguistics.

Let’s think about the kind of activity that this standard envisions our having students do. Identifying the functions of verbals in sentences would require students to be able to do, among other things, something like this:

Underline the gerund phrases in the following sentences and tell whether each is functioning as a subject, direct object, indirect object, object of a preposition, predicate nominative, retained object, subjective complement, objective complement, or appositive of any of these.

That’s what’s entailed by just PART of the “standard.” And since the “standard” just mentions verbals generally and not any of the many forms that these can take, one doesn’t know whether it covers, for example, infinitives used without the infinitive marker to, so-called “bare infinitives,” as in “Let there be peace.” (Compare “John wanted there to be peace.”) Obviously, just meeting this ONE “standard” would require YEARS of explicit, formal instruction in syntax, and what contemporary linguistic science teaches us is that all of that instruction would be completely irrelevant to students being able to formulate and comprehend sentences. The authors of the new “standards,” paid for by Bill Gates and foisted upon the country with almost no vetting, clearly, sadly, tragically, understood nothing of this.

Contemporary linguistic science teaches that grammatical competence is acquired not through explicit instruction in grammatical forms but, rather, automatically (fluently and unconsciously) via the operation of an internal mechanism dedicated to such learning. A specific example will make the general point clear:

If you are a native speaker of English, you know that

the green, great dragon

“sounds weird” (e.g., is ungrammatical) and that

the great, green dragon

“sounds fine” (e.g., is grammatical).

That’s because, based on the ambient linguistic environment in which you came of age, you intuited, automatically, without your being aware that you were doing so, a complex set of rules governing the proper ordering of adjectives in a series. No one taught you, explicitly, these rules governing the order of precedence of adjectives in English, and the chances are good that you cannot even state the rules that you nonetheless “know,” but in the sense that you have acquired those rules unconsciously and automatically and apply them unconsciously and automatically. And what’s true of this set of rules is true of all but a minuscule portion of the grammar of a language that a speaker “knows”—that he or she can use. Knowledge of grammar is like knowledge of how to walk. It is not conscious knowledge. The walker did not learn to do so by studying the physics of motion and the operation of motor neurons, bones, and muscles. The brain and body are designed in such a way as to do these things automatically. The same is true, contemporary linguistic science teaches us, of the learning of the grammar of a language. Speakers and writers of English follow hundreds of thousands of rules, such as the C-command condition on the binding of anaphors (a key component of the syntax of languages worldwide), that they know nothing about explicitly. Following this rule, they will say that “The president may blame himself” but will never say “Supporters of the president may blame himself,”[3] which violates the rule, even though they were never taught the rule explicitly and could not explain, unless they have had an introductory Syntax course, what the rule is that they have been following all their lives. Since the ground-breaking work by Noam Chomsky in the 1950s, we have over the past sixty years developed a robust scientific model of how the grammar of a language is acquired. It is acquired unconsciously and automatically by an internal language acquisition mechanism.

Like many great thinkers, Chomsky started with a simple question, asking himself how it is possible that most children gain a reasonable degree of mastery over something as complicated as a spoken language. With almost no direct instruction, almost every child learns, within a few years’ time, enough of his or her language to be able to communicate with ease most of what he or she wishes to communicate. This learning seems not to be correlated with the child’s general intelligence and fails to occur only when there is a physical problem with the child’s brain or in conditions of deprivation in which the child has limited exposure to language. If one looks scientifically at what a child knows of his or her language at the age of, say, six or seven, it turns out that that knowledge is extraordinarily complex. Furthermore, almost all of what the child “knows” has not been directly and explicitly taught. For example, long before going to school and without being taught what direct objects and objects of prepositions are, an English- speaking child understands that the first sentence, below, “sounds right” and that the second sentence does not.

Like many great thinkers, Chomsky started with a simple question, asking himself how it is possible that most children gain a reasonable degree of mastery over something as complicated as a spoken language. With almost no direct instruction, almost every child learns, within a few years’ time, enough of his or her language to be able to communicate with ease most of what he or she wishes to communicate. This learning seems not to be correlated with the child’s general intelligence and fails to occur only when there is a physical problem with the child’s brain or in conditions of deprivation in which the child has limited exposure to language. If one looks scientifically at what a child knows of his or her language at the age of, say, six or seven, it turns out that that knowledge is extraordinarily complex. Furthermore, almost all of what the child “knows” has not been directly and explicitly taught. For example, long before going to school and without being taught what direct objects and objects of prepositions are, an English- speaking child understands that the first sentence, below, “sounds right” and that the second sentence does not.

Tokyo is Japan’s capital.

Tokyo Japan’s capital is.

In other words, on some level, the English-speaking child “knows” that direct objects follow (and do not precede) the verbs that govern them, even though he or she has no clue what objects and verbs are. The Japanese child, in contrast, “knows” just as well that in Japanese objects precede (and do not follow) the verbs that govern them. (The sentence, in Japanese, is “Tookyoo wa Nihon no shuto desu,” i.e., Tokyo SUBJECT PARTICLE Japan POSSESSIVE PARTICLE capital is.) So, imagine that the sentences, above, were translated word-by-word into Japanese and that the word order were retained. To a Japanese child, the word order of the first of these sentences would sound quite strange, while the word order of the second would be unexceptional—just the opposite from English. English is a head-first language, in which the head of a grammatical phrase precedes its objects and complements (so, in the verb phrase is Japan’s capital, the verb is comes first). Japanese is a head-last language, in which the head of a grammatical phrase follows its objects and complements (so, in the Japanese phrase, the verb comes last). Kids are not taught this. They are born with part of the grammar (the fact that there are heads, objects, and complements, for example) already hard wired into their heads. Then, based on their ambient linguistic environments, they automatically set certain parameters of the hard-wired internal grammar, such as head position. Children do not learn such rules by being taught them any more than a whale learns to echolocate by attending echolocation classes.

Chomsky’s central insight was that in order for a child to be able to learn a spoken language with such rapidity and thoroughness, that child must be born with large portions of a universal grammar of language already hardwired into his or her head. So, for example, the neural mechanisms that provide for classification of items from the stream of speech into verbs and prepositions and objects, and those mechanisms that allow verbs and prepositions to govern their objects, are inborn. They are part of the equipment, developed over millennia of evolution, with which human children come into the world. Then, when a child hears a particular language, English or Japanese, for example, certain parameters of the inborn language mechanism, such as the position of objects with respect to their governors, are set by a completely unconscious, autonomic process that is itself part of the innate neural machinery for language learning.

Because the learning of a grammar is done automatically and unconsciously by the brain, explicit instruction in grammatical forms of the kind called for by the Common [sic] Core [sic] State [sic] Standard [sic] quoted above is largely irrelevant to learning to speak and read. And, in fact, such instruction is most likely going to get in the way, much as if one tried to teach a child to walk by making him or her memorize the names of the relevant muscles, nerves, and skeletal structures or tried to teach a baseball player how to hit by teaching him or her calculus to describe the aerodynamics of baseballs in motion. In other words, the national “standard” is based on a prescientific understanding of how grammar is acquired. This should be a national scandal. It’s as though we had new standards for tactics for the U.S. Navy that warned against the possibility of sailing off the edge of the Earth.

To return to the main topic, we have seen, above, that grammatical fluency and automaticity is an essential prerequisite to reading comprehension. So, if such fluency and automaticity is not gained via explicit instruction, how is it to be acquired? The answer is quite simple: The child has to be exposed to an ambient linguistic environment containing increasingly complex syntactic structures so that the language acquisition device in the brain has the material on which to work to put together a model of the language.

So, why do some kids have, early on, a great deal of syntactic competence while other kids do not? The answer should be obvious from the foregoing. Some were raised in syntactically rich linguistic environments, and some were not. In 2003, Betty Hart and Todd R. Risley of the University of Kansas published a study showing that students from low-income families were exposed, before the age of three, to 30 million fewer words (to a lot less language) than were students from high-income families. A later, much larger attempted replication found a 4 million-word gap. Unfortunately, these studies did not report disparities in total number and frequency of lexemes and in the syntactic complexity of the ambient linguistic environment.[4] Grad students: Hart and Risley focused on vocabulary, but note that some superb doctoral theses could be written on the differences in the syntactic and morphological completeness of the grammars internalized by kids raised in poverty and wealth. Kids living in extreme poverty often aren’t talked to much. They are talked at. An impoverished diet of imperatives (“Shut up!” “Go play outside!”) does not make for linguistic nutritional adequacy.

Shockingly, however, what reading comprehension “specialists” commonly do in their classrooms mirrors what happens to kids from impoverished families and is precisely the opposite of what is required by the language acquisition device, or LAD. Instead of providing syntactically complex materials as part of the child’s ambient linguistic environment so that the LAD can “learn” those forms automatically and incorporate them into the child’s working syntax, these reading “professionals” intentionally use with children what are known as leveled readers. These intentionally contain short (and thus, usually, syntactically impoverished) sentences that will come out “at grade level” according to simplistic (and simple-minded) “readability formulas” like Lexile and Flesch-Kincaid. The readability formulas used to “level” the texts put before children vary in minor details, but almost all are based on sentence length and word frequency (how frequently the words used in the text occur in some language collection known as a corpus). Shorter sentences are, of course, statistically likely to be syntactically simple. So, as a direct result of the method of text selection, complex syntactic forms are, de facto, banished from textbooks and other reading materials used in reading classes. Teachers go off to education schools to take their master’s degrees and doctorates in reading, where they learn to use such formulas to ensure that reading is “on grade level,” and by using such formulas, they inadvertently deprive kids of precisely the material that they need to be exposed to in order for their LADs to do their work. After years of exposure to nothing but texts that have been intentionally syntactically impoverished, the students have not developed the necessary syntactic fluency for adult reading. When confronted with real-world texts, with their embedded relative and subordinate clauses, verbal phrases, appositives, absolute constructions, correlative constructions, and so on, they can’t make heads or tails of what is being said because the sentences are syntactically opaque. A sentence from the Declaration of Independence, The Scarlet Letter, a legal document, or a technical manual might as well be written in Swahili or Klingon or Linear B.

What can be done to ensure that students develop syntactic fluency? I am not suggesting that students be given texts too difficult for them to comprehend, obviously. I am saying that they must be given texts that are challenging syntactically—that present them with syntactic forms that they cannot, at their stage of development, completely parse automatically (that is, in the argot of Education professors, after Vygotsky, texts that are syntactically at kids’ “Zone of Proximal Development”), for it is only by this means that the innate grammar-learning mechanism can operate to expand the student’s syntactic range. But even before that, kids who come from linguistically impoverished environments–the ones who have almost never had the experience of having conversations with adults and arrive in school barely articulate in their spoken language–need remedial exposure to spoken language rich in morphological and syntactic forms (and in related, domain-specific vocabulary–more about that later). The second of these is almost never done. Here are a few techniques: Identify, via diagnostic testing, the common SPOKEN morphological and syntactic forms that the student has not acquired and does not use. In conversation with students, use increasingly morphological and syntactically complex language to which the child has not been exposed. (This is not done systematically now, but it needs to be.) Present students with texts that are routinely just above their current level of syntactic decoding ability. Have them listen to syntactically complex texts (because syntactic decoding of spoken language outpaces syntactic decoding of written language). Have them memorize passages containing complex syntactic constructions. Have them do sentence combining and sentence expansion exercises. And most of all, as soon as they can begin to do so, with difficulty, have them read real-world materials—novels and essays and nonfiction books that have NOT been leveled but that are high interest enough to repay their effort. That such materials will contain difficult-to-parse constructions is precisely the point. Those are the materials on which the LAD works to acquire internal grammatical competence.

NB: It is valuable to teach kids some very basic traditional grammar–the names of the parts of speech and terms like sentence and phrase and clause. These provide useful terminology for referring to parts of writing by students and others. Some sentence diagramming using tree diagrams can be useful for teaching students to write more complex sentences, and sentence combining, expansion, and rearrangement exercises (in which kids are encouraged to create new sentences from old) are invaluable for teaching sentence variety. In addition, study of the grammar of a language is interesting in and of itself, and I recommend this for older students. What cannot be stressed enough, however, is that teaching an explicit formal model of a grammar to kids will have almost no effect on either their grammatical competence (on their internalized grammar of their language) or on the frequency of errors in their speech and writing. Unfortunately, many English teachers, having themselves learned the older, prescientific, folk theory of traditional grammar, as opposed to contemporary generative syntax, think that when they choose a standard usage over a nonstandard one, they are applying their knowledge of traditional grammar rather than their internalized grammatical competence. They aren’t, and they are confused about this. Equally unfortunately, many others, on the opposite side of the grammar wars, don’t recognize the value of learning some of the traditional model for the purpose of having a rough-and-ready language for discussing language. That’s also a problem. So, some advice: yes, teach BASIC traditional grammar to provide a rough language for talking about language, but know why you are doing this teaching–not to instill grammatical competence, which is acquired automatically, unconsciously, from exposure to the right linguistic environment, but to provide that basic language for talking about language.

Vocabulary and World Knowledge

So, with regard to the grammatical fluency component of reading comprehension, the state of our pedagogy is abysmal. We’ve had things precisely backward. In the Whole Language days, we avoided explicit instruction in phonics when it was precisely explicit instruction that was necessary for most kids because of the inadequacy of the innate, internal language-learning mechanism with regard to the task of interpreting sound-symbol correspondences. Today, if we are hewing closely to the new “standards,” we do explicit instruction in grammar, when the internal language-learning mechanism is set up to learn grammar automatically, without explicit instruction.

Are things any better with regard to the vocabulary component of comprehension? Sadly, no. The most common way in which vocabulary instruction is approached in the United States today is by giving students a list of “difficult” (low-frequency) words taken from a selection. So, for example, a student might be assigned the reading of Chapter 1 of Wuthering Heights and be given this list of words from the chapter:

Causeway

Deuce

Ejaculation

Gaudily

Laconic

Manifestation

Misanthropist

Morose

Peevish

Penetralia

Perseverance

Phlegm

Physiognomy

Prudential

Reserve

Signet

Slovenly

Soliloquise

Vis-à-vis

Students are then asked to look the words up in the dictionary or in a glossary, define them, write sentences using them, and memorize them for a vocabulary quiz. As with grammar, the preferred approach involves explicit instruction.

Now, the thing that should strike you, in looking at that list, taken, as it is, out of the context of the novel, is that they might as well be words taken at random. The task facing the student is quite similar to memorizing a random list of telephone numbers.

Other commonly used instructional techniques include teaching students to do word analysis by having them memorize Greek and Latin prefixes, suffixes, and roots and teaching them to use context clues such as examples, synonyms, antonyms, and definitions. These persist despite abundant evidence that they are, for the most part, not the means by which people acquire new vocabulary. They can be used for that, certainly, but they aren’t the primary means by which vocabulary is acquired.

Again, these instructional approaches fly in the face of the established science of language acquisition. We now know, because linguists have studied this, that almost all of the vocabulary that an adult uses (active vocabulary) and understands (passive vocabulary) is learned unconsciously, without explicit instruction. Far less than one percent of adult vocabulary has been acquired by direct, explicit instruction because direct, explicit instruction is not the means by which vocabulary is acquired. As with grammar, there is a way in which the language-learning mechanism in the brain is set up to learn vocabulary, and that way is not via explicit instruction. So, how do people learn vocabulary? A person takes a painting class at the Y. In the course of the coming weeks, the people around him or her use, in that class, terms like gesso, chiaroscuro, stippling, filbert brush, titanium white, and so on, and, in the absence of explicit instruction, the speaker picks the words up because people’s brains are built to acquire vocabulary automatically in semantic networks in meaningful contexts. Vocabulary is a variety of world knowledge, and like other world knowledge, it is added, incidentally, to the network of knowledge that one has about a context in which it was actually used. For vocabulary to be acquired and retained, it has to be learned in the context of other vocabulary and world-knowledge having to do with a particular domain. Human brains are connection machines. Knowledge is easily acquired and retained if it is connected to existing knowledge. The message for educators is clear: If you want students to learn vocabulary, skip the explicit vocabulary instruction and concentrate, instead, on extended exposure to knowledge in particular domains and enable the students to acquire, in context, the vocabulary native to that domain. The focus has to be on the knowledge domain—on turtles or Egypt or Medieval balladry or whatever—and the vocabulary has to be learned incidentally and in batches of semantically related terms because that is how vocabulary is actually learned. It’s how the brain is set up to learn new words. As it stands now, students are subjected to many, many thousands of hours of explicit instruction in random vocabulary items, with the result that far less than one percent of the vocabulary that they actually learn was acquired by this means. The opportunity cost of this heedless approach is staggering.

My teachers should have ridden with Jesse James

For all the time they stole from me.

–Richard Brautigan

With regard to the vocabulary from Wuthering Heights, teachers are well advised to give the kids a list of the most difficult words, along with their meanings and some examples of their use, before the reading, and spend a little time gong over those. Or, they can read passages with the kids and stop, from time to time, to clarify the meaning of a word in its immediate context. However, teachers should skip the attendant fruitless activities–the asking kids to memorize the list of words and definitions for a quiz or test.

Kairos and World Knowledge

Texts exist in context. If someone says, “We need to tie up the loose ends here,” it makes a difference whether the speaker is a macramé instructor or Tony Soprano. Is the statement about pieces of string or about a mob hit? The context matters. Comprehending the sentence—understanding what it means—depends crucially on the context in which it is uttered. The same is true of almost all language.

The ancient Greeks used the term kairos to refer to a speaker’s sensitivity to his or her audience, to the occasion, and to the immediate context of the utterance. I’ll be using it, here, in a slightly expanded sense to refer to all the extra-textual stuff that goes into understanding a text. For years, reading comprehension teachers have been told to begin the reading of a text by “activating their student’s prior knowledge.” Millions of teachers dutifully learned this “strategy” and attempted to apply it in their classrooms even though a moment’s reflection would have revealed it to be completely absurd. If a student already has the relevant background knowledge to understand a text, then it will not need to be “activated.” It will simply be there. And if the student does NOT have the relevant background knowledge, no amount of having students tell what they already know will supply it. That said, and here we have yet another example of educators half hearing what scientists have been saying, cognitive scientists like Daniel Willingham of the University of Virginia and the education theorist E.D. Hirsch, Jr., have shown beyond any reasonable doubt that background knowledge—what the writer assumes that the reader already knows—is one of the great keys to reading comprehension. Let’s consider an example. My students’ eleventh-grade literature textbook contains a passage about how Arthur Miller wrote The Crucible in reaction to the Army-McCarthy hearings of 1954. The passage mentions people being hauled before the Senate Subcommittee on Investigations and being accused of being Communists. It goes on to say that Miller was concerned by the hysteria and guilt-by-association attendant to these hearings and wrote the play to show how the same sort of thing occurred during the Salem Witch Trials of 1692. Now, if the students reading that do not know the background—what a Communist is; that the United States is a Capitalist country; that Communism and Capitalism are antagonistic; that in the 1950s, the United States was involved in a Cold War with the Communist Soviet Union; that the Soviet Union had vowed to bring down the American system; that certain Senators and Congressmen in the 1950s were concerned about Communist infiltration of the media, the government, and the armed services; what a subcommittee is; what a hearing is; and that the Subcommittee on Investigations attempted to identify Communist sympathizers, then the passage in the text will be meaningless. In short, comprehension depends critically on world knowledge. Without the relevant background knowledge, comprehension cannot occur. A student cannot read Milton or Dante with comprehension if he or she is ignorant of the Bible and won’t comprehend the title of George Bernard Shaw’s play about Professor Higgins and Liza if he or she is ignorant of the Greek myth in which Pygmalion falls in love with a statue. Consider this opaque text from Dylan Thomas:

The twelve triangles of the cherub wind

This impenetrable text becomes crystal clear when one realizes that Thomas is referring to old maps that represented the winds as cherubs whose breath—the winds—inscribed triangles across the maps.[5] One can’t begin to understand Plato’s allegory of the cave without understanding that he was highly influenced by Greek mathematics, recognized that perfect forms (like a point or a perfect triangle) did not exist in the world but did exist in the mind, used a single word (psyche) for both mind and spirit, and thus thought of anything perfect (and thus, he thought, good) as existing in a separate, spiritual plane that could be accessed through mental/spiritual activity. One has to have a lot of information about the background—the concepts available to Plato and what he was concerned with—to make any sense at all of his bizarre little story. Domains of knowledge, from auto mechanics to the growing of orchids to theodicy and dirigible driving all have their associated vocabulary—not just jargon but words and phrases that appear with particular frequency and particular meaning within them. And knowledge of this vocabulary is not a matter of possession of a bunch of definitions taken in the abstract but, rather, possession of an understanding of how those words and phrases are used and in what contexts within the relevant domain. Life coaches and physicists use the word potential in related but distinct ways and about different objects. Understanding what is meant by the word, in a text, requires, in addition to knowledge of its definition, knowledge of how it is used in the subset of the world that is the knowledge domain of the text. Furthermore, the ability to use a term actively involves mastering not only its definition but also its inflected and derivative forms, something that is learned not through explicit, rote study but through use in context. A student hasn’t really learned the word imply unless he or she can properly use such inflected forms as implying, implied, and implies as well as such derivative forms as implication, and one learns those forms, really learns them, only through repeated use in a context. Simply memorizing the definition for a test is a recipe for forgetting.

This impenetrable text becomes crystal clear when one realizes that Thomas is referring to old maps that represented the winds as cherubs whose breath—the winds—inscribed triangles across the maps.[5] One can’t begin to understand Plato’s allegory of the cave without understanding that he was highly influenced by Greek mathematics, recognized that perfect forms (like a point or a perfect triangle) did not exist in the world but did exist in the mind, used a single word (psyche) for both mind and spirit, and thus thought of anything perfect (and thus, he thought, good) as existing in a separate, spiritual plane that could be accessed through mental/spiritual activity. One has to have a lot of information about the background—the concepts available to Plato and what he was concerned with—to make any sense at all of his bizarre little story. Domains of knowledge, from auto mechanics to the growing of orchids to theodicy and dirigible driving all have their associated vocabulary—not just jargon but words and phrases that appear with particular frequency and particular meaning within them. And knowledge of this vocabulary is not a matter of possession of a bunch of definitions taken in the abstract but, rather, possession of an understanding of how those words and phrases are used and in what contexts within the relevant domain. Life coaches and physicists use the word potential in related but distinct ways and about different objects. Understanding what is meant by the word, in a text, requires, in addition to knowledge of its definition, knowledge of how it is used in the subset of the world that is the knowledge domain of the text. Furthermore, the ability to use a term actively involves mastering not only its definition but also its inflected and derivative forms, something that is learned not through explicit, rote study but through use in context. A student hasn’t really learned the word imply unless he or she can properly use such inflected forms as implying, implied, and implies as well as such derivative forms as implication, and one learns those forms, really learns them, only through repeated use in a context. Simply memorizing the definition for a test is a recipe for forgetting.

A Summary of the Prerequisites for Reading Comprehension

Decoding ability—phonics and grammatical fluency—is, of course, prerequisite to comprehension. The sound-symbol correspondences of the written language must be mastered and the grammatical forms used in the language internalized from the spoken linguistic environment before comprehension is possible. The same is true of domain-specific world knowledge—knowledge about Communists, the Bible, Greek myths, old maps, geometrical forms, or whatever it is that the author is taking for granted that the reader already knows, including the vocabulary used in that context, or domain. E.D. Hirsch, Jr., has written eloquently and persuasively on precisely this subject in numerous works, including The Schools We Need and The Knowledge Deficit. (See also Reading Instruction: The Two Keys, by University of Virginia English professor Matthew Davis.) The reader is referred to those works for further information. Suffice it to say that the teacher must ensure that students have the relevant background knowledge, including domain-specific vocabulary, to understand what they are being asked to read and that instruction should be focused on extended time spent in particular knowledge domains so that students can build the bodies of knowledge that they need for comprehending texts in the future. New knowledge needs a hook to hang on. That hook is other knowledge in the relevant knowledge domain.

That ought to be obvious. However, today, reading instruction has devolved into isolated practice of “comprehension strategies” using short texts taken absolutely at random—a snippet of text here on invasive species, a snippet of text there on Harriet Tubman. But brains are built to acquire knowledge in connected networks, and the hundreds of thousands of hours spent doing this practice of strategies applied to random, isolated texts is time wasted. More about that later.

So, knowledge is essential to comprehension. But there are other extra-textual matters—other parts of the overall kairos of the text—that are also essential. Among these are genre and a whole raft of conventions of usage—idioms, transitional devices and turns, figures of speech, rhetorical techniques, manuscript formatting, and so on. So, for example, comprehending Sir Philip Sydney’s Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia or one of William Blake’s Songs of Innocence might require knowledge of the conventions of the genre of pastoral—that lambs represent innocence, that shepherds are uncorrupted by city life, that spring represents youth and rebirth, and so on. The semantic component of language is highly conventional. Understanding a poem often requires familiarity with conventional symbol systems like that which relates the cycles of the seasons to the life cycle (spring/youth, summer/maturity, autumn/age, winter/death). One has to know the convention, or one is lost.

Given all this, one would expect that reading comprehension instructors were devoting their time to a) ensuring that students have automaticity in phonetic and grammatical decoding, b) building vocabulary and world knowledge through extended work in critical knowledge domains, and c) acquainting students with the conventions of various genres and the primary literary and rhetorical conventions. After all, that’s what reading comprehension requires. But if you made such an assumption, you would be wrong. What reading comprehension teachers are doing, instead, is spending their time teaching “reading strategies.”

The Devolution of Reading Comprehension Instruction and Assessment

Back in 1984, Palinscar and Brown wrote a highly influential paper about something they called “reciprocal learning.”[6] They suggested, in that paper, that teachers conducting reading circles encourage dialogue about texts by having students do prediction, ask questions, clarify the text, and summarize. Excellent advice. But this little paper had an enormously detrimental unintended effect on the professional education community. All groups are naturally protective of their own turf. The paper by Palinscar and Brown had handed members of the professional education community a definition of their turf: You see, we do, after all, have a unique, respectable, scientific field of our own that justifies our existence: we are the keepers of “strategies” for learning. The reading community, in particular, embraced this notion wholeheartedly. Reading comprehension instruction became MOSTLY about teaching reading strategies, and an industry for identifying reading strategies and teaching those emerged. The vast, complex field of reading comprehension was narrowed to a few precepts: teach kids

to identify the main idea and supporting details,

to identify sequences,

to identify cause and effect relationships,

to make predictions,

to make inferences,

to use context clues,

to identify text elements.

In the real world, outside school, a strategy is a broad approach to accomplishing a goal (e.g., greater market penetration; increased share price; greater profitability). In EdSpeak, weirdly, a strategy is any particular thing whatsoever that one might do to advance toward a goal (what in the real world would be called a tactic). It’s sadly common for people in education to use words imprecisely like this—to borrow a term and then use it improperly. Consider the term benchmark. In the real world, a benchmark is a standard reflecting the highest performance in a given industry. So, for example, the highest read-write time for a disc drive achieved by any manufacturer is a benchmark, or goal, for other disc drive manufacturers to meet. In education, a benchmark is any sort of interim evaluation. Educators confused the goal (the benchmark) with the method of evaluating achievement of the goal. Education schools are bastions of such sloppy thinking—confusion of means and ends, misapplication of concepts, and so on. There are brilliant people in education schools, but they work among many who are simply passing along unexamined habits of the tribe.

Throughout American K-12 education, in the late 1980s, we started seeing curriculum materials organized around teaching some variant of the list of “reading comprehension strategies” given above. Where before a student might do a lesson on reading Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” he or she would now do a lesson on Making Predictions, and any random snippet of text that contained some examples of predictions, as long as it was “on grade level,” would be a worthy object of study.

One problem with working at such a high level of abstraction—of having our lessons be about, say, “making inferences,” is that the abstraction reifies, it hypostatizes. It combines apples and shoelaces and football teams under a single term and creates a false belief that some particular thing—not an enormous range of disparate phenomena—is referred to by the abstraction. In the years after Palinscar and Brown’s paper, educational publishers produced hundreds of thousands of lessons on “Making Inferences,” and one can look through all of them, in vain, for any sign of awareness on the part of the lessons’ creators that inference is enormously varied and that “making proper inferences” involves an enormous amount of learning that is specific to inferences of different kinds. There are, in fact, whole sciences devoted to the various types of inference—deduction, induction, and abduction—and whole sciences devoted to specific problems within each. The question of how to “make an inference” is extraordinarily complex, and a great deal human attention has been given to it over the centuries, and a quick glance at any of the hundreds of thousands of Making Inferences lessons in our textbooks and in papers about reading strategies by education professors will reveal that almost nothing of what is actually known about this subject has found its way into our instruction. If professional educators were really interested in teaching their students how to “make inferences,” then they would, themselves, take the trouble to learn some propositional and predicate logic so that they would understand what deductive inference is about. They would have taken the trouble to learn some basic probability and techniques for hypothesis testing so that they would understand the tools of inductive and abductive inference. But they haven’t done this because it’s difficult, and so, when they write their papers and create their lessons about “making inferences,” they are doing this in blissful ignorance of what making inferences really means and, importantly, of the key concepts that would be useful for students to know about making inferences that are reasonable. This is but one example of how, over the past few decades, a façade, a veneer of scientific respectability has been erected in the field of “English language arts” that has precious little real value.

I bring up the issue of instruction in making inferences in order to make a more general point—the professional education establishment, and especially that part of it that concerns itself with English language arts and reading instruction, has retreated into dealing in poorly conceived generalization and abstraction. Reading comprehension instruction, in particular, has DEVOLVED into the teaching of reading strategies, and those strategies are not much more than puffery and vagueness. To borrow Gertrude Stein’s phrase, there is no there there. No kid walks away from his or her Making Inferences lesson with any substantive learning, with any world knowledge or concept or set of procedures that can actually be applied in order to determine what kind of inference a particular one is and whether that inference is reasonable. A kid does not learn, for example, that some approaches to making inductive inferences include looking at historical frequency, analyzing propensities, making systematic observations and tallies, calculating the probabilities, conducting a A/B split survey, holding a focus group, and performing a Gedankenexperiment or an actual experiment involving a control group and an experimental group. Why? Because one has to learn and teach a lot of complex material in order to do these things at all, and professional education folks have decided, oddly, that they can teach making inferences without, themselves, learning about what kinds of inferences there are, how one can make them rationally, and how one evaluates the various kinds.

Though reading comprehension instruction has now almost completely devolved into the teaching of “reading comprehension strategies,” those strategies do not, themselves, hold up to close inspection. They all exemplify a fundamental kind of error that philosophers call a “category error”–a mistaken belief that one kind of thing is like and so belongs in the same category as some completely different kind of thing. Reading comprehension “specialists” now speak of learning “comprehension strategies,” as though recognizing the main idea, making inferences, and so on, were discrete, monolithic, invariant skills that one can learn, akin to learning how to sew on a button or learning how to carry a number when adding, but the “reading comprehension strategies” are nothing like that. Being able to identify the main idea of a given piece of prose, poetry, or drama is NOT a general, universally applicable procedural skill like being able to carry out the standard algorithm for multiplying multi-digit numbers, and placing them into the same category (“skill”) is an example of the logical fallacy known as a category error.

When you see a list of the skills to be tested for math and the skills to be tested in ELA–that is, when you look at a list of “standards”–it’s important that you understand that there are very, very different KINDS of thing on those lists, the one for math and the one for English. These are not only as different as are apples and oranges, they are as different as an apple is from a hope for the future or the pattern of freckles on Socrates’s forehead or the square root of negative one. They are different sorts of thing ALTOGETHER because the math skills are discrete, monolithic, and invariant, and those “reading strategies” are not.

Let me illustrate the point about “the main idea.”

What is the main idea of the following?

The ready to hand is encountered within the world. The Being of this entity, readiness to hand, thus stands in some ontological relationship toward the world and toward worldhood. In anything ready-to-hand, the world is always ‘there.’ Whenever we encounter anything, the world has already been previously discovered, though not thematically.[7]

Now, note that this passage would have a pretty low Lexile level. It doesn’t contain a lot of difficult (long, complicated, low-frequency) words, and the difficult words (ontological, ready-to-hand, thematically) can be explained. It doesn’t contain long or syntactically complicated sentences. But the chances are good that unless you are familiar with continental philosophy, you will have NO CLUE WHATSOEVER what this passage is saying. In order for you to understand the main idea of this passage, you would need, at a minimum, an introduction to the philosophical problems that Heidegger is addressing in the passage. In other words, you would have to have a lot of world knowledge about continental philosophy. Otherwise, the passage will be impenetrable to you. No general “finding-the-main-idea skill” will help you to make sense of the passage.

Now, what is the main idea of the following?

One of the limits of reality

Presents itself in Oley when the hay,

Baked through long days, is piled in mows. It is

A land too ripe for enigmas, too serene.

There the distant fails the clairvoyant eye.

Things stop in that direction and since they stop

The direction stops and we accept what is

As good. The utmost must be good and is

And is our fortune and honey hived in the trees

And mingling of colors at a festival.[8]

Again, the language is not that difficult. One can easily define the less frequent words–enigmas, serene, clairvoyant, and utmost. But that’s not going to help you figure out what the “main idea” here is. For that, the royal road is an introduction to the kinds of concerns that Wallace Stevens took up in his poetry. If you know from his other work that Stevens wrote, time and time again, about the failure of our abstractions to account for the concrete facts of the world and about our tendency to live in our abstractions rather than in the real world, if you know that Stevens was distrustful of abstractions of all kinds—religious, political, philosophical, and so on, then the passage will make sense to you. If you don’t, well, good luck.

Now, notice that what is involved in figuring out the main idea of each of these passages is entirely different. Oh, sure, there are similarities between the passages. Both are passages in English. Both deal with a philosophical idea. Actually, they both deal with the same philosophical idea. But in the one case, to grasp the main idea, you have to be familiar with a lot of Continental philosophy and with the kinds of problems that such philosophy addresses. In the other, you need to be able to recognize that Stevens is revisiting what is, for him, a recurring theme.

This is the key point: there is no one procedure–no one finding the main idea procedure–that I can teach you that will enable to you to determine what each passage, and any other passage taken at random from a piece of writing, means.

In other words, no instruction in some general finding-the-main-idea skill is going to help you, usually, to find the main idea. There’s a reason for that, lol. There is no “general finding the main idea skill!” Thousands and thousands of contemporary “reading lessons” notwithstanding, that such a thing exists is an UTTER FICTION. The “general finding-the-main-idea skill” is as fictional as were Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s fairies in the garden.

In other words, no instruction in some general finding-the-main-idea skill is going to help you, usually, to find the main idea. There’s a reason for that, lol. There is no “general finding the main idea skill!” Thousands and thousands of contemporary “reading lessons” notwithstanding, that such a thing exists is an UTTER FICTION. The “general finding-the-main-idea skill” is as fictional as were Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s fairies in the garden.

Finding the main idea is context dependent in a way that adding multi-digit numbers isn’t. It makes no difference whether you are adding 462 and 23 or 1842 and 748, you are going to follow the same procedure and draw upon the same class of facts. Not so with “finding the main idea.” There is no magical procedure for main-idea-finding that applies to all texts and scoots around the necessity of engaging with a particular text—decoding it; parsing its morphology and syntax automatically, unconsciously, and fluidly; applying world knowledge to understanding it; recognizing its context and conventions; and then generalizing about it or recognizing that some statement within it encapsulates that idea. Sure, occasionally one will encounter, in the real world, a puerile piece of writing of the five-paragraph theme variety that states its main idea in an introduction or conclusion. One can teach students, for a few limited types of texts, to do that. But most texts in the real world contain no such idea readily identifiable using a particular procedure. Hedda Gabler contains no thesis statement. Neither does the Gettysburg Address or, typically, an entry in The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Identifying the main idea of each text–IF there is one–is a tall order and requires, for each, unique prerequisites. Schooling in reading comprehension should teach kids to make sense of real-world writing, and writing in the real world does not take the form of five-paragraph themes with the main idea neatly tucked in at the conclusion of the introductory paragraph. And as long as we continue cooking up pieces of fake writing for use in exercises on finding the main idea in those, we are perpetuating a myth.

And, of course, attempting to test for possession of this mythical general finding-the-main-idea faculty that is being magically transmitted to students via “reading comprehension instruction” is like requiring people to bag and bring home any other sort of mythical entity–a unicorn, Pegasus, or the golden apples from the tree at the edge of the world.